MOCA presents Adrián Villar Rojas: The Theater of Disappearance, a site-specific installation inside The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA’s warehouse space. Villar Rojas (b. 1980, Rosario, Argentina) has built a singular practice by creating environments and objects that seem to be in search of their place in time. Villar Rojas’s interventions beckon viewers to consider fragments that exist in a slippery space between the future, the past, and an alternate reality in the present. With his post-human artworks, Villar Rojas posits the question: What happens after the end of art?

Villar Rojas’s method is emphatically site-specific, requiring a deployment of project-based teams who work on-site for extended periods of time to fabricate the installations. Long before the beginning of a project, he makes a series of site visits to immerse himself in the social, cultural, geographical, and, above all, institutional environment where he will work. This inherently nomadic process echoes his own personal trajectory as an itinerant artist, one of constant travel and engagement with a diversity of sites across the globe. Villar Rojas’s approach is two-pronged. First, before beginning to insert objects into a given space, he considers the ways in which a space might be modified or adapted in relation to the incoming exhibition. Employing a keen sense of spatial awareness, he considers how visitors move through the space, their relationship to scale, and the affective potential of lighting. This sensitivity to the poetics of space is at the core of Villar Rojas’s practice, and no work can begin on a site before these considerations are taken into account, resulting in modifications to the existing space. He can mandate small changes, such as to the size of doorways or color of walls, or structural changes, such as moving the placement of windows or adjusting floor heights. Villar Rojas sees each project as an educational opportunity not only for those who visit the exhibition but equally so for himself. The institutions are given an opportunity, in turn, to reconsider the use of their own architectural assets, filtered or focused through the lens of Villar Rojas’s highly attuned sensitivities.

More than purely aesthetic, this invasive dynamic allows Villar Rojas to develop an almost—in his own words—“parasitic relationship” with the institution; it is in this radical dialogue and exchange where both the artist-parasite and the institution-host explore the limits of what is possible and what is not, what is acceptable and what is not, what is negotiable and what is not. Ethics and politics, no less than agency and decision-making, are at stake in the project, opening a series of tough questions: When and where does a project actually begin? What if an invisible series of housekeeping-like tasks, part of a wide range of circumstances that have been dismissed since the very beginning of art as secondary, is, on the contrary, key to producing that optical illusion we call a “work of art”? What if we made a radical inversion and took the work of art as an excuse to do the housekeeping?

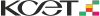

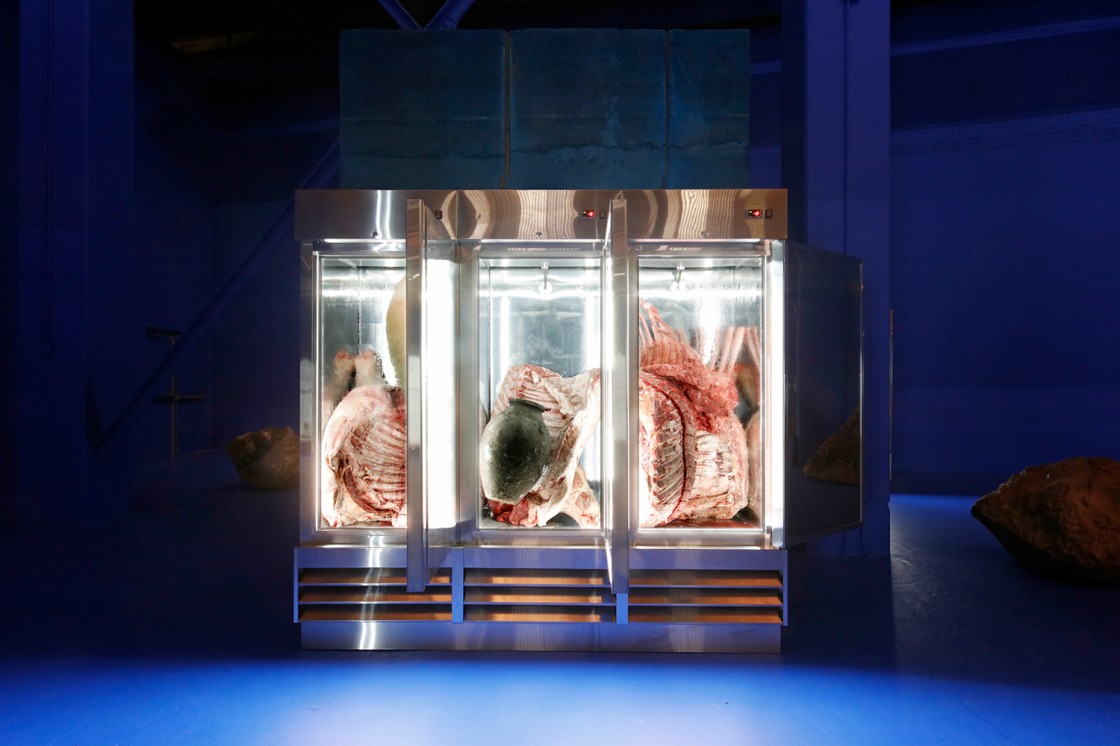

Once Villar Rojas has tuned the exhibition space to meet his goals, the second phase of his process can begin. Although what the artist and his collaborators introduce into the exhibition spaces could ostensibly be called sculpture, it differs due to their functions in a variety of modes. The constructions, produced on-site during installation, take form in concrete, stone, raw clay, and organic and inorganic things that keep on changing over time through growth and decomposition. Old tennis shoes and fruit peels find themselves embedded in the floor of a gallery, or are seen as part of the geological strata that form a tower of differently colored layers of concrete. Villar Rojas determines the forms and objects that will be included in these juxtapositions of organic and inorganic, permanent and impermanent materials. The artist attempts to view these man-made fossils as an alien might, with no preconceived associations and complete horizontality—a profound equalization of art and non-art materials. The visitor becomes a witness to the entropy of these objects as they decompose or become obsolete over the course of the exhibition. For Villar Rojas, the gallery visitor arrives halfway through the process, somewhere between the project’s creation and decomposition.

Although what Villar Rojas will introduce into The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA’s exhibition space could reasonably be understood as sculpture, it also acts as the material basis for his ontological inquiries. In an effort to undermine the critical terms that often enable and sustain the commercial and institutional art world, such as endurance, reproducibility, tradability, and transportability, everything in Villar Rojas’s project is carefully planned to show its temporal side: What is doomed to disappearance, what cannot be preserved. Villar Rojas unveils this spatial and material fragility to remind us of the fleeting and minuscule presence of our own existence in the universe.

For his project at MOCA, Villar Rojas will radically transform the Little Tokyo space, employing dramatic architectural and aesthetic shifts. In preparation for the installation, Villar Rojas spent a great deal of time exploring technologies used in Hollywood special effects and was struck by the universal digitization of the industry. From his perspective, it echoes a kind of post-human world dominated by technology, and in response, he will create an environment in The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA that is at once tactile and ephemeral, otherworldly and utterly human. Villar Rojas will use remaining materials and surviving bits of “art” from projects produced across the globe and recycle them into new “art,” this time tailor-made for The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA. Petrified wood from Turin, stratified columns from Sharjah, and silicone molds from Istanbul will not be reinstalled as what they once were but instead will have a second, unpredictable life. These elements will journey from “art” to “non-art” and back again to “art,” reinforcing their impermanence and our own in relation to our attempts to ascribe imperishable meanings and values to the world around us.

The exhibition will be accompanied by a full-color publication with an introduction by MOCA Research Assistant for Latin American Art Bryan Barcena, and a conversation between Villar Rojas and MOCA Chief Curator Helen Molesworth. Vividly illustrated using computer renderings and drawings, the publication provides a glimpse into the process by which an Adrián Villar Rojas project comes to fruition.

Curators: Bryan Barcena and Helen Molesworth

Lead support is provided by the Aileen Getty Foundation, kurimanzutto, Mexico City, Maurice Marciano, Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, Paris, London, and

Major support is provided by Charlie Pohlad and the Pohlad Family, and Maria Seferian.

Generous support is provided by Suzanne and David Johnson, and Kaitlyn and Mike Krieger.

Additional support is provided by the Brener Family.

Exhibitions at MOCA are supported by the MOCA Fund for Exhibitions with lead annual support provided by Sydney Holland, founder of the Sydney D. Holland Foundation. Generous funding is also provided by Allison and Larry Berg, Delta Air Lines, and Jerri and Dr. Steven Nagelberg.

In-kind media support is provided by KCRW 89.9FM and