Introducing: Lorraine O’Grady and Juliana Huxtable, Part 1

A conversation between artists Lorraine O’Grady and Juliana Huxtable. The dialogue took place by phone from O’Grady and Huxtable’s respective studios in New York City. This is part one of a two-part discussion and the first time the artists have spoken.

Lorraine O’Grady: Juliana, I have to tell you something, Jarrett Earnest interviewed me and said he hoped you and I could meet, but you know, I didn’t ask him why he thought it would be a good idea. [both laugh] To be honest, I have to confess that because I didn’t know much about you or about your work before this, I’d succumbed to the stereotype, I was captivated by your image and didn’t look at your mind at first. But now I totally understand why people want to put us together—it’s almost like talking to myself. [JH laughs] Do you know what I mean?!

Juliana Huxtable: Definitely.

LO: I often try to imagine what I would be like if I had been born about the time you were born, and now I realize what I would be like. I’d be like you! I see so much of our attitudes as being similar that it’s kind of scary. But then I wondered why you thought it was going to be a good idea?

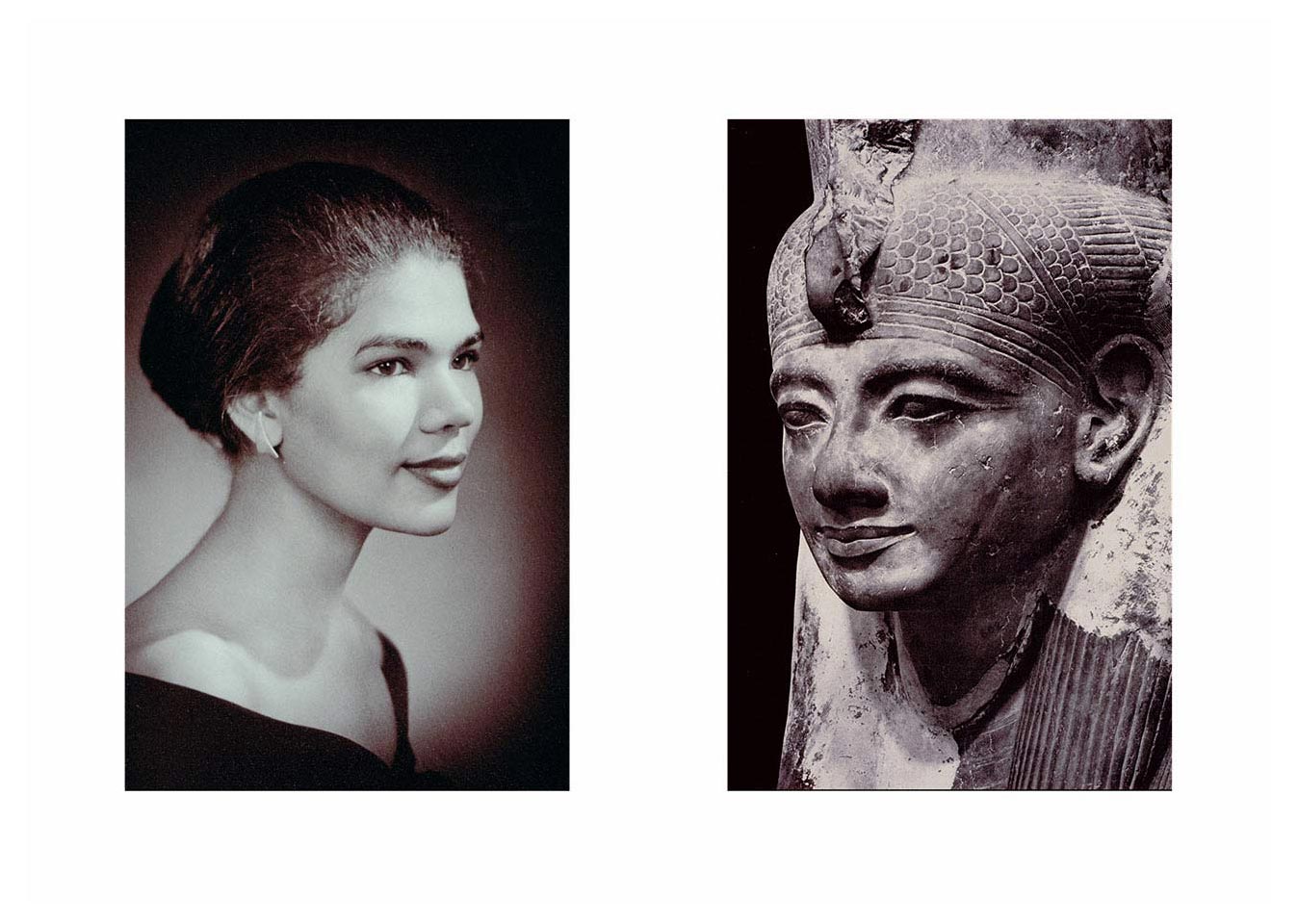

JH: Well, I didn’t study art; at one point I had the intent, but I was really turned off by my school’s program and generally distanced myself from studying studio art. So I studied literature and gender studies and found myself in my practice as an artist, not necessarily unexpectedly, but without a really concrete knowledge of an art history. I remember actively seeking out an art history relevant to me. I saw a piece of Miscegenated Family Album at the Brooklyn Museum. When I found your work, I was so excited and so happy—really fascinated by the idea that you were able to navigate the practice that you have. Initially, I was fascinated by the idea of taking a conceptual approach to Egyptology, how your work dealt with ideas of racial violence related to perceptions of Egypt, and the right of someone of the African diaspora to engage or identify with Egyptian history. On a larger level, I was excited by your floating between text and a sort of personal and documentary imagery. You were also using performance as a way of approaching text. It seems—and I don’t know if you perceive your work in this way—that performance has been a way of animating text and taking text out of the referential structures that it’s easy for them to get trapped in otherwise. It’s similar to the way artists see a necessary relationship to Western art history in some ways. So I guess that’s a starting point.

Lorraine O'Grady, Miscegenated Family Album: 04. SISTERS IV (L: DEVONIA'S SISTER LORRAINE, R: NEFERTITI'S SISTER MUTNEDJMET), 1980/94, Silver dye bleach photograph (Cibachrome), 20 x 16 in., courtesy of the artist

LO: Well, I totally agree with that because I did come to art as a writer, and I still think of myself as, I don’t know what really, I use the phrase “writing in space.” In fact, I constructed Miscegenated Family Album as a novel in space. Sometimes I wonder if what I do is visual art. It’s like some strange hybrid between the two [art and writing]. Some of my most important influences are literary. I came into art so late, after doing so many other things. I was further out from the history of art when I began than you were I think. [both laugh] You’d studied art history seriously for at least a moment before you gave it up. But I hadn’t done that. I had been teaching a kind of art history at the School of Visual Arts—the Surrealists, Dadaists, and the Futurists, but as part of a course on the literature of those movements…you know, the manifestoes of [Filippo Tommaso] Marinetti, Tristan Tzara, André Breton, and those guys, and the writings of Marcel Duchamp. Duchamp’s ideas seriously influenced me. But at that time I didn’t have a systematic integration of the field as a whole. For example, I knew the situation that we as black artists were in at that moment, but not all that had led up to the extreme segregation of the 1980s. When I look back, I think I understood the moment itself and had a narrowly focused idea of how the current ideas in art could be appropriated by myself and others like me. Perhaps that led to more originality, I don’t know.

One thing that I wanted to talk to you about was––how to put it? Besides making critiques, without intending to, I seemed to be constructing myths. Even Art Is… turned out that way. It was accidental, because it was done the last year before crack hit Harlem. That was the last moment you could do a performance like that, collect photographs in that way. But even an accidental myth is still a myth. Now I wonder if I was making art in a way that you might find boring or irrelevant to making art today. For me, it’s been about making a body of work. Well, maybe not a body of work so much as individual works that are complete and self-sufficient. I’ve had this kind of traditional relationship to myth and form. I knew about mythology from the time I was five and went to a classical school. And then I also grew up High Episcopalian, with all those rituals and the words of the Book of Common Prayer, which at that time hadn’t changed since the days of Shakespeare and King James. I feel like whatever I do goes toward myth whether I want it to or not and ends up private and layered. But I think what you’re doing may be the opposite of mythology.

JH: Mhm.

LO: Maybe it’s my age, but I’m private enough that I can’t imagine putting so many photographs of myself on the Internet and still living my life. [both laugh] I think I’d be too worried, or perhaps too curious. I don’t know whether there’s a question in all of that or not. Was there a question?

JH: I think there are threads of different and related questions. In terms of mythology and how it relates to my work, my mother—and my father to the degree that he was present and had any influence on me––held on to this idea that they were projecting this sort of mythological status onto their performance of upward mobility, onto their education…it’s actually where I got the name Huxtable. So both of them had this crossover between their own sort of “biographical” (for lack of a better term) existence as people in the world and their ties to this almost overwhelming symbolic—and for my mother heavily religious in a Southern Baptist type of way—idea of themselves. Growing up, certain iconographies were very important. At my mother’s command, we had no white Santa Claus. Santa Claus was black, all the elves were black, any biblical representation was black or perhaps multicultural. The Jesus in my multicultural bible “for children of color” had a Jheri curl.

In terms of how my work became visible, I started out writing online. I had a blog and people followed it. It was this weird space in which I was just sharing a lot of things, but also establishing a trail of how I was thinking. Then it started to coalesce into images and texts of my own making. I didn’t think of them as art necessarily; I wasn’t so conscious of exactly what was happening. They were just exercises in thinking through the ideas that I was excited by.

LO: But you were thinking them through online?

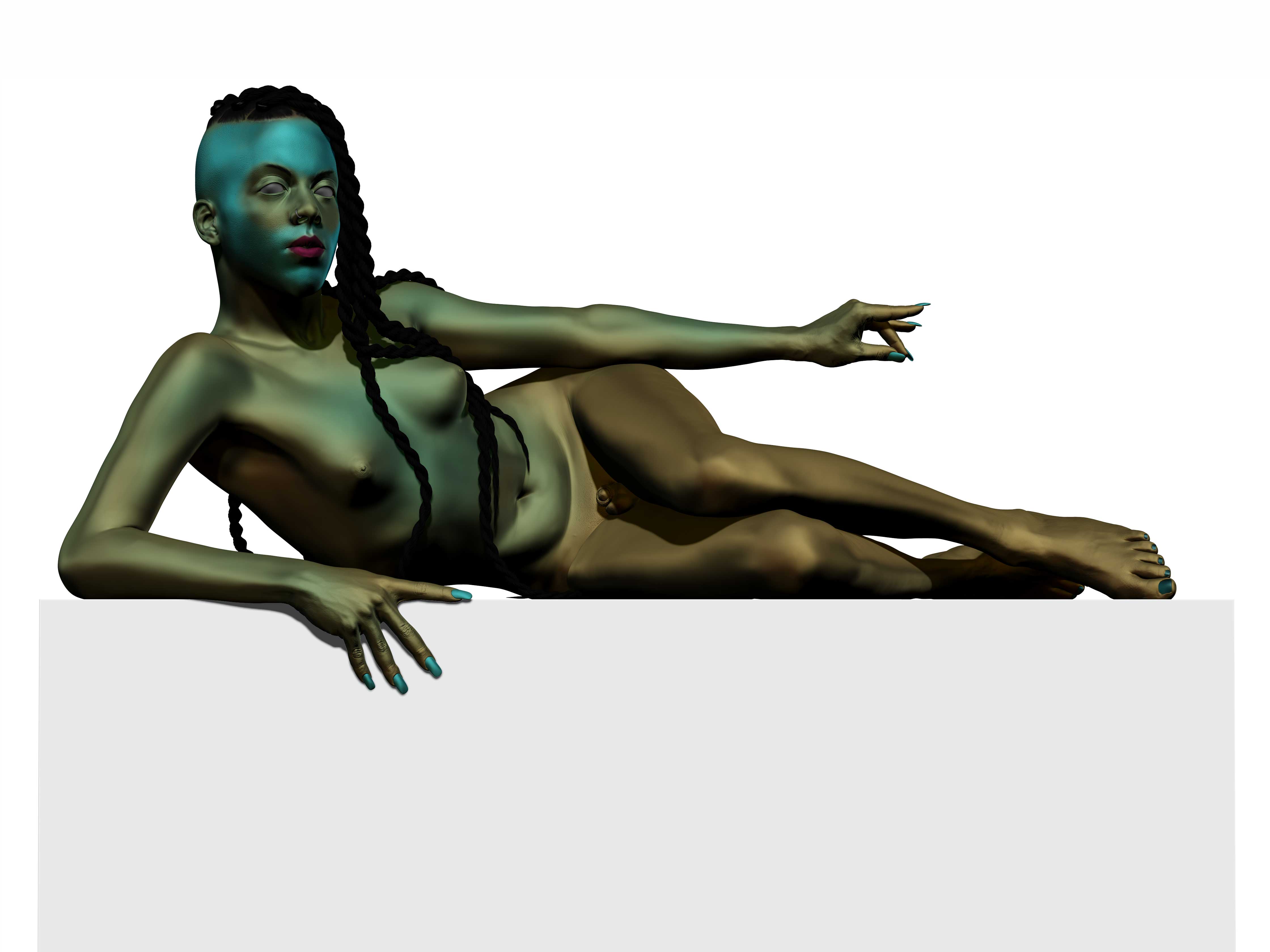

JH: Yeah, I was thinking them through online, and it happened as I was on the cusp of becoming highly visible on social media in a larger public sense. By the time that my visual work—especially the work involving the images of myself—started to circulate, I was also aware of myself—at like twenty-four, twenty-five years old—as already being sort of…fantastical. Mythical feels like an intense word for me to use in reference to myself, but I became very cognizant of my work as an extension of myself and as a vehicle for other people to see themselves and their own possibility, and this is amplified by social media. That began to inform my work. I became obsessed with the Nuwaubian Nation and how they were taking these weird strains of science fiction and Egyptology, merging them together with a liberation theology and creating a mythological system of references…ideas dealing with a kind of racial crisis, perhaps even if they didn’t know what the crisis was. I also wasn’t sure of exactly what I was dealing with or whether it was a crisis. I did feel, nonetheless, that I was creating these images that allowed me to perform the role of the mythological figure in different ways.

LO: I think that you’re being seen in your own time in this way that is similar to the way I’m being seen after my own time, and I wonder how that affects your process?

JH: At one point it felt less about me singularly, back when I was primarily producing things online and doing smaller group shows in the context of the different communities that I was part of on the Internet. At that point, the potentials and ramifications of the online didn’t really affect my work. If anything we were all mutually projecting these ideas of each other, simply reflecting what’s always happening. But especially after the [2015] New Museum Triennial’s inclusion of Frank Benson’s sculpture [of me] and my own work and what it signified in terms of visibility, I had a growing sense of anxiety. It was in that moment that performance became a really clear, powerful, and necessary way for me to work through all of that. I think there is a prevailing idea of performance, a kind of romantic notion of performance being about putting your body in a public or social context to create a provocation, which isn’t what I do. This is partially why I look up to so many of the performances that you’ve done. Performance offered a powerful way to deal with questions of self-erasure or presence, tempting an audience with the idea that I am performing to enable their consumption of my image or my body—and then to ultimately refuse that. Text and video and all of this media become modes of abstracting presence or abstracting myself in the present. And so right now performance feels like a way of dealing with the sort of aftermath of a cultural moment.

Frank Benson, Juliana, 2014, Digital renderings of painted Accura® Xtreme Plastic rapid prototype

LO: Kimberly Drew says some really interesting things. She speaks about how the Internet provides a space for non-majority artists to make our work known on its own terms. In my case, I had actually done all of this work, but [I did so] when it wasn’t part of the extremely limited recuperation of black artists that happened in the late ’80s, it had to exist in the limbo of my imagination for the next twenty years. The Internet gave me the opportunity to put it out there and have it live again in this archival way—the first website went up in 2008. But you know, even though I put the work up as something dead, it’s turned out to live in a more active way than I could have imagined. While for me, it’s very distant because the making was so long ago, it’s alive for others. I’m too concerned with what I’m doing now.

Last year I got a grant from Creative Capital for a new performance. It’s Mlle Bourgeoise Noire 35 Years Later, what she’s turned into. The character is an avatar of that previous avatar if you know what I mean. It relates to the way I used to do performance, I think, but in an off-kilter way. It’s a kind of drag. The costume is kind of hiding me. But the main problem I face is that it’s being done in a totally new moment, an Internet, smartphone moment. And a moment when I’m a known artist, not the unknown that I once was. When I did Mlle Bourgeoise Noire, no one knew she was coming—I could do it as a totally guerrilla performance. Now everyone wants to know about her avatar in advance. But if anybody had known MBN was coming, there wouldn’t have been any surprise and neither she nor I would still be here, right? So I feel I can’t talk about it, that I have to be withholding, at least for now. Right now, we’re developing the new persona in the studio, to see how it looks, moves.

But, I don’t know, the current cultural moment feels more—if not narrative—perhaps more serial than the earlier single actions that I did. Maybe after the character appears for a while, it will have another life where I develop it further on the Internet. Not that I live there myself; I have no social media presence at all, you know? I have a highly developed website—I even did the information architecture myself—but I’m not on Facebook or Instagram or any of the others. So, I don’t really know how successfully those platforms can be used as an exercise in creativity for something that isn’t life-based, just fictional work. Maybe I should just try and see what happens.

JH: In my ideal world, I would be able to control and decide how and when to document performances that I’ve done or work that I’ve made online. The way that it currently exists kind of puts artists—at least for me—in this crisis where I don’t really have a choice in the matter. If I don’t participate in the construction of my own presence online, it’s totally in the hands of others.

LO: Are you a gallery artist, by the way? Do you have a gallery?

JH: I do not. Everything that I’ve done has been me up to this point. I have my first gallery show soon, but I work on my own, which has also been kind of a crazy experience because of presumptions about protection that artists have. But I’ve produced on my own, and with the gracious assistance of friends and curators that have helped me out.

LO: [laughs] I became a gallery artist about the same time that I put the website up. One of the things the gallery thought was smart was that I’d controlled the existence and availability of my images. But I hadn’t tried to do that! What happened was I didn’t have any video tapes of my performances, just a limited number of photos. So I was accidentally lucky! In the end, the reduced amount of material meant nobody could do to my work what you’ve indicated you fear: no one could control my existence or distort my existence online. I’m not sure, but I suspect even negative critiques couldn’t do that. Bad or faulty interpretations may enter the work’s history, but I don’t think they undermine the work. At least, because of the initial shaping I did, I’m hoping that the work can just sit there and wait for another interpretation.

JH: Right.

LO: Some things about your situation seem so different from mine that I have to struggle to translate. But then there are all the underlying things that don’t seem to change. For example, I found it difficult to watch that panel[“Transgender in the Mainstream”] at Art Basel Miami.

JH: Oh my God, they totally messed up that panel…

LO: To me, it was just so much the same old story. It was a three-to-two ratio, which is certainly better than the old three-to-one or three-to-zero ratio. But the framework…some of the panelists at Art Basel used the phrase “multiple methods” multiple times, and yet I still felt a subtle undertow of privileging abstraction over representation. It reminded me a bit of what I’d written about in Olympia’s Maid. [laughs] Just when we were beginning to be able to examine our own subjectivity, others were declaring subjectivity dead, of no interest because it was socially-constructed. But how could we declare it dead until we’d had a chance, or taken the time to examine it live? Another thing that bothered me was that doing the panel at a commercial art fair seemed like a chew-it-up, spit-it-out use of trans. Nothing could be properly interrogated, either “trans” or “mainstream.”

JH: Right, and I felt like the violence of that panel was absurd. The term “mainstream” has a way of announcing something as dead, at least in the context of an Art Basel panel. It dealt with none of the dynamics that we should actually be talking about, which have yet to be worked through. I’m so angry at that panel.

LO: I think what you said to Jarrett [Earnest] was right on target, you know, that there’s still so much unexplored work to be done on bodies, that wanting to move from representation to abstraction really is a way of avoiding dealing with bodies, and especially a way to avoid dealing with bodies that are discomforting. Your statement seemed to directly parallel what I was saying in Olympia’s Maid. There, I couldn’t help feeling that two concerns might be connected, that the discomfort caused by black people’s exploration of their subjectivity might somehow be connected to postmodern thought’s declaration of subjectivity as a dead construct. As I watched the panel, I wondered if trans bodies were not discomforting, there might not be the need to go into abstraction to protect mainstream sensibilities, to provide a path to safety. As if safety should be a motif in art, either for the maker or the viewer.

JH: Right, right. There’s a rush to push it to abstraction when it’s not a white dude creating his own interpretation.

LO: Exactly.

JH: In terms of why you turned to images of Egypt, was that intended as a dismissal of or an alternative to prevailing models of cultural history? Perhaps even fashioning an idea of representation or history of representation that doesn’t rely on a Western history of visual culture?

LO: Well, I can still remember the day my third-grade teacher pulled down the map of Africa over the chalkboard for a geography lesson. She waved her long wooden pointer and said, “Children, this is Africa! All except this…which is Egypt and part of the Middle East.” Even then, I felt something was being taken from me. And that feeling stayed until two years after my sister died, and I went on a trip to Cairo. I found myself surrounded by people who looked like me. It was the first time in my life that had happened, you know? I always thought that [my sister] Devonia looked a bit like Nefertiti, but that was the moment I began to think about hybridity as a concept. I saw Egypt as a hybrid culture.

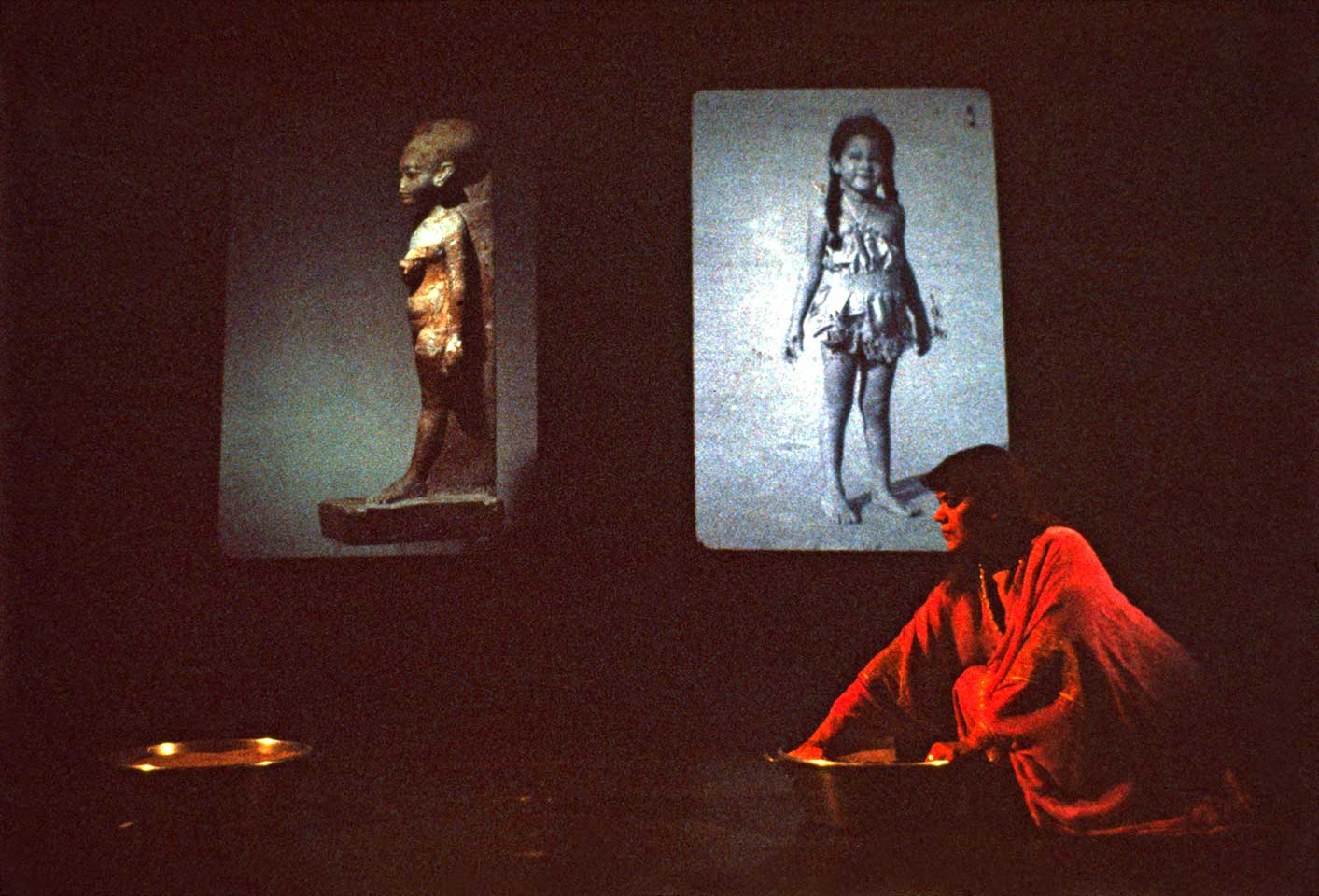

Lorraine O'Grady, Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline, 1980, Performance, Just Above Midtown Gallery, courtesy of the artist

For sure, some people see Afrocentrism in the performance Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline and the wall installation I made from it later, Miscegenated Family Album—but it wasn’t that. If anything, it was a kind of hybrid-centrism. I felt in the coming together of Lower and Upper Egypt, northern and southern Egypt, that two distinct regions and cultures, the Middle East and Africa, had come together. And that they had been joined the way so much else is joined, by an act of violence. One conquered the other. In this case, the conquerors were from the South. The Nubian dynasties conquered the Northern ones. I think most students agree that contemporary-styled racism never took hold in ancient Egypt. It was sort of preempted. Looked at from that point of view, I saw ancient Egypt as a sort of utopian society compared to current cultures. There are other ways of looking at Egypt that may not be so utopian, but certainly from that perspective, I thought it was. But the genesis of the work itself was much more personal. I’d had a rather troubled relation with my sister. In the end, I used what I could imagine as Nefertiti’s troubled relation to her younger sister to work out my relationship with my sister Devonia. You could say that the piece was overdetermined, like everything I do. It was political and personal, about sisters but also about mothers and daughters, about cultural theory and beauty.

JH: That makes sense. You mentioned in another interview, Black Athena…

LO: Right, the Martin Bernal opus…

JH: …that what you were doing predated that. I was obsessed with Chancellor Williams’ The Destruction of Black Civilization and Bernal’s Black Athena growing up. I found them in high school.

LO: You actually found the Bernal books and you read them?

JH: There’s a PDF site online that had excerpts. It wasn’t the whole book, but I had The Destruction of Black Civilization, which pulls heavily on similar ideas and similar histories.

LO: Did you read Cheikh Anta Diop?

JH: No.

LO: He was a Senegalese scholar who wrote about the connections of Ancient Egyptian civilization to southern African civilization in a way that made a big impact. It really clarified certain things for me. He was the first to say that everything we think of as Egyptian—the structure of kingship, the nature of religion, not to mention hieroglyphics and pyramids—all of that was basically the product of the Southern dynasties, and since they were coming out of Nubia and perhaps points further south than that, it’s impossible to comprehend ancient Egypt without understanding its foundation in southern African culture. But Cheikh Anta Diop’s book was what I would call the Afrocentric argument. That wasn’t what interested me the most about Egypt. What interested me was the meeting of the Middle East and Africa in that one place…I mean, I admire the accomplishments of southern Egypt, but I don’t think Egypt became “Egypt”—the glorious Egypt—until the two halves were united.

JH: Right.

LO: It may be romantic of me, but I saw it as an example of what true hybridism could accomplish. I have a similar romantic response to al-Andalus, Moorish-occupied Spain.

JH: Right.

LO: I also think Egypt was just the most beautiful culture, don’t you think so?

JH: Yeah, it’s gorgeous.

LO: I want to wear that clothing forever! [laughs] It looks like it must feel incredible. And I love that they had hair problems, and they just solved them by shaving it all off and wearing wigs and headdresses.

JH: I really like the idea of thinking of or appreciating Egypt as a hybrid culture because for a long time I had a hard time feeling like I could identify with or find pride in Egypt. It felt like it had to be about Afrocentrism, you know, totally loaded with derogatory ideas of revisionism and all of the attacks that were launched on this scholarship coming from a non-European and specifically diasporic angle. It was as if it was dangling in front of me and to go for it, to fully engage it, was something I refused myself as a masochistic gesture.

LO: Well I don’t know that I’ve really tried to make coherent, convincing arguments for Egypt’s hybridism. People still look at that work and dismiss it as Afrocentric without understanding that it was not that at all. But you can’t do everything. Sometimes, it’s all I can do to do the work. You just hope that if you drop breadcrumbs, someone will pick up the trail. I believe Nefertiti and her family, like my sister Devonia and her family, were formed by generations of miscegenation. But I do recognize the difference between royal marriage politics and slavery in the Western Hemisphere. Still, what interests me is that, in both cases, ancient Egypt and the Americas, this lived hybridization or miscegenation created new cultures. I really do think we live in a new culture here. And with the continued pressures of diaspora, it’s a culture that is still evolving, being reproduced by a hybridization that is now way beyond that weirdly matched world of slaves and masters in the “old” Western hemisphere.

JH: Yeah.

LO: We’re living in some strange world that’s…

JH: …a really insane in-between.

LO: Yeah. I feel that way, too. In my case, it gets complicated because people think I’m advocating for interracial sex or they think I’m in favor of colorism, which is something I’ve actually been fighting against my whole life. I feel that the complexities and the dangers of the arguments in my work make it more interesting. I think because my work contains so much ambiguity, it’s always going to be the subject of approval or disapproval if you know what I mean.

JH: Right.

LO: But I have to leave the complexity and the ambiguity in there because that’s a part of it. I have to make the arguments that I have to make, you know.

JH: Right. It can be difficult for people to engage with this, at least when I’ve done performances or texts that have dealt with this taboo. Growing up in the South, a lot of my early interactions had a particular curiosity to them; there was something that stimulated me visually and symbolically about the exchange of desire between myself and these “country,” presumably off-limits, white boys that I had romances with. When I deal with what that means or how that imagination was charged with ideas that aren’t just about desiring to overcome some sort of slave-master dichotomy, it’s a conversation that can get shockingly conservative.

LO: Yeah, well…I think John Waters has called it “the last taboo.”

JH: Right.

LO: His movies kept trying to deal with it, but it is the last taboo even though people don’t say so.

JH: Yeah.

LO: It’s hard to find ways to deal with it suggestively in a way that’s generative and doesn’t close it down. The response is always to try to close it down, but if there’s something in the work that is still generative that can fight back, that’s what you want.

JH: Right. How do you see—thinking in terms of hybridity—the way that the Internet has amplified discussions around cultural appropriation? Sometimes there are these acts that I think are totally egregious, and other times I think it’s less a question of appropriation than emblematic of the culture that we’re in, which has been accelerated by image production and distribution. This acceleration has perhaps created generations of people whose only notions of culture come from what they’re feeding themselves and generating online. It’s something alien and foreign to them, and so when it crosses over into real interactions between different and othered bodies, it becomes complicated in a different way. How do you see those sort of questions of being amplified or not amplified or being mutated by the net?

LO: Doesn’t it depend on who’s doing the appropriation in some ways? I mean we have this whole history of colonialist appropriation. And, to me, one of the things that black artists are engaged in is their own appropriation of white culture. I don’t know if it effectively answers the other form of appropriation, but it certainly complicates one’s view of appropriation, when the appropriated begins to appropriate.

JH: Right, right.

LO: And you know, I’m not sure that moment is being given the freedom it requires to grow and to have its fullest impact. It’s amazing to me how quickly discussions can be shut down. The discussion of the subjects we’ve been engaging, all these things can be shut down if you don’t fight, if you don’t have the weapons with which to fight. I mean, for example, the accusations against Ta-Nehisi Coates of pessimism…I have to confess that I’m a bit on his side myself.

JH: In what sense?

LO: That, basically, the struggle may never be finally won, or at least not in our lifetimes.

JH: Oh, yeah.

LO: So as Coates says, the struggle itself has to become the source of pleasure.

JH: Mhm.

LO: One of the things Edward Said wrote in Orientalism is that, even in academia, you find that you are always having to go back to the beginning because the drag of resistance is so great, things have to be repeated over and over and over again. They’re not proven, transmitted as truth once and for all. Because power has the infinite capacity to resist, you find yourself making the same arguments over and over and over. You’re in this loop. I think that’s where many black artists are now. We’re in this repetition loop. How to get out of it is the question. We still don’t seem to be saying much that hasn’t been said before by other black artists. Is what we say “sticking” better than before? That’s harder to see.

JH: Taking that as a context, one of the quotes that really stuck with me from reading through your interviews and essays is; “I will always be grateful to performance for providing me the freedom and safety to work through my ideas; I had the advantage of being able to look forward, instead of glancing over my shoulder at the audience, the critics, or even art history.” I think you were talking about the Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline performance. That registered with me, with my own relationship to performance. I really feel a freedom to not have to deal in the conversations that painters have to have. So many painters that are dealing in questions of representation have to deal the burden of the art historical reference. They have to deal with the fact that the work itself exists and the work itself has to carry the responsibility for its own historical presence in some way. I was curious what you meant in terms of the freedom of performance, or performance as a space of possibility specifically in the context of what you were just sort of saying about sort of the cycle.

LO: Performance was not overburdened with history and that itself was freeing. I’m wondering if the presence of my work has already become a drag? [both laugh] Do you feel you have to fight me off? [laughs]

JH: I don’t!

LO: That’s good, but feel free, feel free to fight! [laughs]

This dialogue was organized by Aria Dean and edited by Aria Dean and Karly Wildenhaus. Special thanks to Marco Kane Braunschweiler.