Introducing: Ann Lauterbach and Lauren Mackler

Ann Lauterbach: This is possibly the strangest phone conversation I have ever had—even before it begins.

Lauren Mackler: Do you hate the phone?

AL: I do hate phones, yes.

LM: Oh no! [laughs]

AL: I actually never talk on the phone anymore except for under duress. [laughs]

LM: Well, let’s see what we can do with the medium.

AL: OK, let’s see what we can do with the medium. How do you want to begin?

LM: I’m not sure. I have so many notes in front of me, so many things I want to talk to you about including “aboutness.” [both laugh]

AL: Well, I’m wonderfully without any preconception whatsoever because I still don’t actually understand what the idea of this is—other than the pleasure of meeting people that are interesting that I don’t already know. But I haven’t discovered yet the pretext, so maybe that will come to light as we go on?

That’s all a very disguised way of saying that I don’t quite know how to think about who you are or what you do. So I could start by being very blunt—who are you and what do you do?

INSTALLATION VIEW OF THE STAND IN (OR A GLASS OF MILK), SEPTEMBER 19–NOVEMBER 19,

INSTALLATION VIEW OF THE STAND IN (OR A GLASS OF MILK), SEPTEMBER 19–NOVEMBER 19,

LM: Of course. Well so, I am Public Fiction essentially, or one part of Public Fiction that is consistent. Public Fiction is an exhibition space for a series of exhibitions, publications, performances, and everything. The way it’s structured is that I do exhibitions on a topic for three months, and during those three months, there’s a range of performances, secret restaurants, talks, screenings and so on based on that theme, and then at the end, there’s a publication. The theme or subject matter serves as a kind of excuse for a multiplicity of voices that come inside and talk about different things. The texts use different aspects of this subject matter as an excuse, which is something that I see in your work as well.

AL: Yes, that’s great. Does all of this happen in various venues or a single venue? Or how does it actually appear in space?

EXTERIOR VIEW OF PUBLIC FICTION STOREFRONT, COURTESY OF PUBLIC FICTION

EXTERIOR VIEW OF PUBLIC FICTION STOREFRONT, COURTESY OF PUBLIC FICTION

LM: That’s a great question because for five years Public Fiction had its own storefront in Highland Park, and the exercise was to use this as a shape-shifting space, so each of the different subject matters or topics at hand transformed this shell into a different thing. But then a few months ago, I left the storefront and decided to become nomadic, partially because I was going to Rome, but also because instead of using the clean slate of an empty space or context, I wanted to try to put these experiments and subject matter into sites that have a preexisting history.

AL: So they become more like insertions or ruptures in the usual habit of the space, is that right?

LM: Exactly.

AL: Is there a political space involved for you in this? Or is there a political element to it—political in the largest sense?

LM: Exactly, in the largest sense. I think a lot about political as in “polis,” which means society. The idea is that art can be a place from where to respond to contemporary concerns or issues that people that have in their moment—essentially using art as a mirroring platform. So the political isn’t necessarily in an activist sense, but more in a contemporary sense.

AL: So it’s political as a part of the social, right? As a kind of continuation of the social?

LM: Exactly. Yesterday I learned that you and I are both the children of journalists, and I think I look a lot at my interest in art or the trajectory of my work as related to that idea of journalism—responding to the contemporary or pulling together a narrative from facts without being factual, although that last part is not journalism.

PUBLIC FICTION JOURNALS

PUBLIC FICTION JOURNALS

AL: Right, well in a very abstract way, I call it “worldness.” You know, I think that one can’t really write without an awareness of worldness. For me, I increasingly use journalism as a whipping post for what I think art isn’t. [laughs]

LM: How do you mean?

AL: Well, I just think that journalists really have to try and convert events and persons into language in a way that’s very oriented towards information, and I am less and less guided by information and more and more interested in what it means for information to become knowledge. This is what I’m most fascinated by—the difference between information and knowledge and whether we can assume that knowledge is just an accumulation of information or whether knowledge is something further or more than that. I guess it means that it’s the interpretative world. So I think for me that more and more I’m interested in art as a kind of interpretation of a world rather than in any way a depiction or capturing of it.

LM: Right, I could see that. I tend to talk about that in terms of fiction because fiction is that kind of transference of information into this other space.

AL: Yes.

LM: You talk a lot about digression in your work now, about tangents. I remember reading a passage in The Night Sky where you talk about digressing into clarity—pulling away from something that’s factual into something that’s more what you described as knowledge in order to look at it with more clarity.

AL: Yes, and maybe there the pulling back is like a camera pulling back and being able to see more or take in more. I used to think about my process as being something like a scanner—scanning for things that would call my attention—and that the work comes as a result of an accumulation of those scans. And I guess the movement of a scan is a little a bit like the movement of a digression.

There’s a constant desire on my part for something like a multiplicity or a plenum or a sense of inexhaustibility of the world. I think I’m interested in that instability rather than the stability. It’s the kind of the opposite of what most people want art to do, which is to distil, and I want it to do the opposite. [laughs] I don’t want it distilled at all—I want to set in motion and make the possibility of the relation between whatever it is that I say or is said in the work. That then opens up the possibility of somebody coming along and making meaning. That’s a kind of cliché at this point, and I’m not disavowing my control over meaning-making. I don’t have that sense of being not there, but the ways in which meanings get made are interesting to me. I’m constantly trying to avoid a certain kind of literalism.

LM: I can definitely see that. I see that especially in your prose writing or in the way that you bring in many voices when you give a talk or write on a subject. I relate—I feel like part of the practice of Public Fiction and its use of the exhibition as a medium is a way to bring together a lot of different voices and a lot of different perspectives. Therefore, it’s not really a conclusion or a thesis on the subject matter but rather a more complicated cloud of responses as perspectives.

AL: Where does that come from in you? Do you know?

LM: I think it’s a love for language—I feel like I get so much out of the process of reading a turn of phrase on a subject matter or looking at an object responding a certain way that I don’t really feel committed to where we arrive but more to the process of gathering around an idea and where we are while we’re doing so.

I think it also comes from being a reader. Not necessarily reading large quantities of things or reading fast. Maybe it’s the opposite of reading fast—reading really slow and having something that really moves inside of you when you’re reading a sentence or something like that.

AL: “Moves inside” is really nice. I did a little tutorial this morning with a couple of undergraduates on this minor genre called “ekphrasis.” It’s based on the desire to transform an image into language, but it’s a very particular kind of image, like painting, and so it’s a very curious secondary space. And we read this amazing chapter—which I hadn’t read before and had given to them—by the French writer Georges Didi-Huberman, do you know him?

LM: No, I don’t. I’d love to read him. What was the chapter?

Fra Angelico, The Annunciation, 1442-1443, fresco, courtesy Wikimedia Commons

AL: The book is called Confronting Images, but the chapter that we read is about the Fra Angelico Annunciation at the Saint Marco in Florence, and it’s an extraordinary consideration of the white in that painting. The reason I’m bringing it up is because in it Didi-Huberman attacks our general history and makes this really quite extraordinary invocation of looking at spaces that involve what he calls “non-knowledge.” One of the ways he talks about non-knowledge is the Freudian idea of a symptom, and he ties the symptom to this place of what he just calls “the movement inside.”

So for him, the gaze of looking at something cannot be immediately made into its linguistic equal or into the sense of recognition. There’s something that is not quite knowable in the full relation to an art object, let’s say. And he ties that unknowableness—that inability to be converted—to a sense of the translatable, to this sort of sense of the habitat, the inner space of the person who has the gaze. I recommend the chapter to you, it’s so beautiful. You will have that feeling that you just described, this kind of stirring inside.

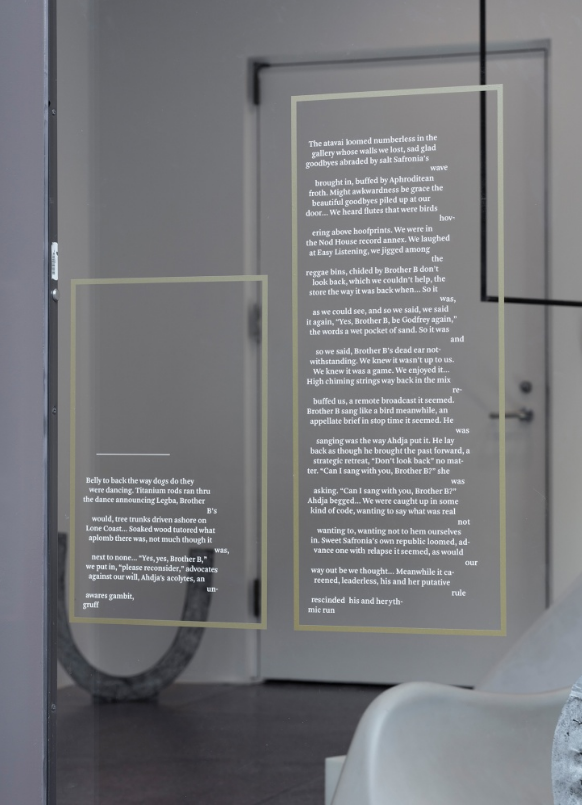

LM: I get a sense for it. It’s very related to the current show [storefront: Public Fiction: The Poet and The Critic, and the missing at MOCA] that I asked you to be a part of because the show is asking artists and writers to psychically fill the space in between objects in an exhibition in the most abstract sense, you know?

AL: I think it’s about a different kind of reading. Obviously, you can read between things as much as you can read the thing itself. I think that’s what you’re interested in, right? It’s the negative space.

LM: Exactly, the negative space, which I think is essentially what an exhibition is. It’s all negative space. The negative space is also the physical position of the public, of the eyes looking at or between the work. It’s also where the contemporary sits or where the now of our timeness sits.

I was just rereading this beautiful introduction to a seminar by [Giorgio] Agamben, “What is the Contemporary?,” that you quoted in one of your talks. It hits so many notes of what this particular project that I’m working on right now is trying to do. It speaks both to how we make something contemporary by the way that we sit and look at in that space in between, and then also how in order to be of a time, you need to be outside or on the periphery of your time. That’s something you’ve written about a lot as well.

AL: I think that place is very meaningful. I’ve discovered that by having opted for that peripheral position in my life as well as a state of precariousness generally, which is another kind of fence. If you align yourself with those spaces, those negative spaces in the cultural sense as well as the physical sense, you find yourself—or at least I find myself—in a fair amount of anguish because it’s not at all the same as the position of being avant-garde. It’s a completely different set of relations that I’m interested in. I’m not interested in the avant-garde at all anymore.

LM: That makes sense because I think Agamben refers to the avant-garde in relation to fashion and trends to a public eye that is relevant and that has the means to be at the center.

AL: Yes, yes.

LM: And I think the position of the periphery is much more interesting. It has critical distance, an ability to look at a time and see what is actually happening.

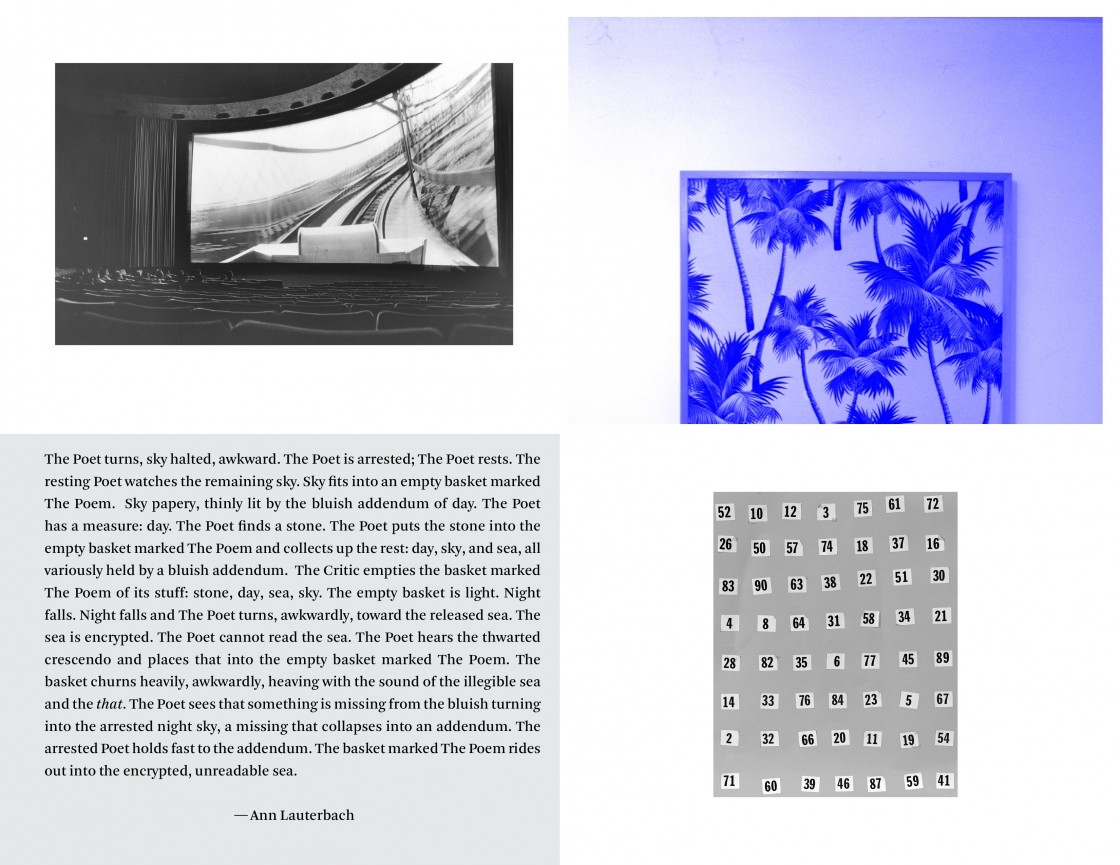

Henri Michaux, Untitled Chinese Ink Drawing, 1961, COURTESY OF TATE

AL: Do you know the work of Henri Michaux? Do you know Michaux and that little book on the Chinese ideogram with the really brilliant afterword by Richard Sieburth? In that little book, Sieburth talks about [Ezra] Pound and [Ernest] Fenollosa and this whole desire for language to be thing-like in its action, to feel like an object in space that has an action. It’s an interesting problem between seeing an event and language, which is probably what you’re coping with [in the exhibition at MOCA].

LM: Yeah, in a way I see that as a starting point, and then the reason to do it now is actually more related to the public or the public experience than to the actual writing. The writing is doing what it does independently of whether or not it’s going to be on a page or in space.

AL: What do you want to happen to the people who go and see or read [the exhibition at MOCA]?

LM: I guess I think it loops back to the beginning of this conversation where we were talking about the movement within. The experience of reading can be something so profoundly monumental but in a really interior space. I want to try to make the act of looking at an exhibition—the act of looking at objects and texts or objects as text—have that same giganticness and intimacy as that act of reading. In a way turning viewing into reading seems like a very political act, you know?

AL: It’s very, very interesting because it seems to me you’re wanting to give the spectator more permission to have an interior—not to feel so exposed and reduced or devoid of interiority in the way that reading always has to assume an interiority of the reader, whereas art objects often don’t assume anything about the viewer or the spectator, right? So maybe what you’re doing is reattaching the eye, not only to the cognitive space of knowing but also to this other space that is more unknown. Maybe you’re trying to draw some kind of analogy between the act of reading and the act of seeing, and that’s an important thing to do.

LM: The reason it seems so important is also in terms of change and the distribution of radical ideas, like how over time radical ideas have taken form in language, objects, actions, and so on. Here, the attempt is to make radical ideas take form in a very interior way.

AL: That’s important. And you use that word distribution—it reminds me of [Jacques] Rancière’s great phrase “the distribution of the sensible.” I love that phrase and his notion of something that again is not still but rather moves across and through space.

LM: The distribution of the sensible?

AL: I think he means that what we experience through our senses is not located in one particular place but can be understood to be across time and across space. It’s a wonderful way of understanding things that happened at a certain time that is then redistributed into other times, into other distribution as it were.

LM: Oh, OK, very interesting.

AL: But it’s really interesting because I think reading is such an indirect relation to our understanding of bodies, right?

LM: Yes, you mean because you have to be away from your body in a way?

AL: Yes, let’s say the language is on a page, and it comes into us, and we locate that meaning-making machine inside of ourselves somewhere between the two. But we don’t have the same experience of looking at the page as we have of looking at a painting, right?

Installation view of storefront: Public Fiction: The Poet and The Critic, and the missing, March 19–June 19, 2016 at MOCA Grand Avenue, courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, photo by Brian Forrest

LM: Mhm, and I think that is part of the public experiment at MOCA—how do you equate this reading of objects in relation to reading and looking at text, or how do you make this kind of back-and-forth in the way that you’re looking. I think that my interest in the experiment comes from a real belief in art’s potential for change or for being read in a different way in relation to the pace at which we are reading things now.

AL: Good luck—I hope you can make that happen! [laughs] We sure do need it badly. Everything that’s happening in the museum world seems to be about speed.

It makes me think a lot about my particular resentment of and dislike for all the wall text that has now become part of the way we have a museum experience. Even though they’re very informative, I also find them extremely invasive, and I want to be left alone with my experience of the work without having this kind of apparatus of information. So it would be very nice if next to somebody’s painting there was a poem or text that had nothing to do with it. [laughs]

LM: Exactly, that’s what I’ve been working on for another show as well! But I remember thinking often of David Foster Wallace’s approach to or description of great writing—that great writing makes the reader feel smart. That seems such a generous approach to the public that could be applied to didactics.

AL: It reminds me of when [Ralph Waldo] Emerson talks about reading and makes this marvelous turn: “In every work of genius we recognize our own rejected thoughts; they come back to us with a certain alienated majesty.” Do you know that phrase by him?

LM: No, but it’s beautiful.

AL: He’s talking about reading and how it comes back when we recognize something, when we’re reading something and we understand it, or we recognize ourselves in a certain alienated majesty.

LM: Exactly. [laughs]

AL: Right? “We recognize our rejected thoughts; they come back to us…” So that’s that wonderful thing of “I thought this.”

LM: And that’s the “we,” that’s the “I.”

AL: That’s so, so great. [both laugh] That’s probably what Foster Wallace was really thinking about. There’s this stream of conditions that we’ve named, and they’re in a kind of fluid relation to each other, right? They’re not static.

Back cover of PF:4, The Lost Issue, 2012, (an aerial view of the 110 / 105 interchange from the Los Angeles Public Library archive), courtesy of Public Fiction

Back cover of PF:4, The Lost Issue, 2012, (an aerial view of the 110 / 105 interchange from the Los Angeles Public Library archive), courtesy of Public Fiction

LM: Mhm. And what a privilege it is to bring together a set of those floating people and pieces and make a common, you know?

AL: Right, right, make a common.

LM: I want to ask you a question that’s on a different topic. Can I? [laughs]

AL: OK, ask the question.

LM: I wanted to ask you about your process of making titles because I think you come up with the most beautiful titles. The title is so much the face of a book or a new body of work or collection, so I want to know about it.

AL: Hmm…I think somewhere along the line a long time ago now, I noticed that prepositions were the key structural piece of the English language. The preposition is the thing that made us understand how one thing is related to another in space as well as in time. So most of my book titles have prepositions in them. It wasn’t so in the beginning, and it wasn’t deliberate, but it just began to happen. I think since most of the work that I do in poems are from these disparate spaces or inputs—different nodes, different events, different references—I need to make a collection of them before I go deep into a poem. In assembling these disparate sources, I need to find something that could not so much hold them together as indicate that elasticity inside of the poem, so I always try to make titles that indicate a way of reading.

The other thing I have often done is put the name of a painter in parentheses, and those are there to let people know that those figures have been part of the substructure or the interior of this poem. I think the best thing I can say about my titles is that they are indicators of the way in which the poem should be approached.

LM: Exactly, which is where my earlier question was going with aboutness anyways. [laughs] It makes sense. The way you include the artists’ names in parenthesis also allows the title to point outside or away from the poem.

AL: That’s exactly right. And I think a lot of my work is about that pointing out, pointing away, or pointing toward, or pointing to say there’s this and that over there.

LM: Which then situates the work in the middle of the world as opposed to in the middle of the page. It points out becomes attached to all these other things.

AL: I have such as a strong spatial imagination that I often think of the poems as if they were in space and literally turning like a weathervane. [laughs] So the pointing is multidirectional, the linearity of language is always something that I have a contentious relationship with because I’m very suspicious of narrativity in general. As you can tell from reading some of my prose, I don’t really even like my prose to tell or do anything but make a series of aspects almost like a prism. I think that’s the best analysis of it, that it’s prismatic. So you take this approach and then you take this approach and then you take this approach and in the center there is something that is almost unnamed, right? It just sits there. [laughs] It’s your point of view or your conclusion.

LM: Right.

AL: It’s an unstable meaning-making machine for sure.

LM: Yeah, because the multiplicity of ways of organizing the meaning is inherent to all meaning. And in these two characters—the poet and the critic—organize content very differently. [laughs]

AL: Right, right. Subject matter is very interesting, complicated thing. Anytime people meet me on an airplane or something and I say I’m a poet then the next question other than “Have you published?” is “What are your poems about?”

LM:. Yes. Aboutness. [both laugh] What have we talked about today?

AL: What haven’t we talked about?

LM: I remember seeing this video that Semiotext(e) produced a few years ago about [Gilles] Deleuze’s L’Abécédaire de Gilles Deleuze. One of the first things he says—I don’t remember the exact turn of phrase—is that talking is so dirty compared to writing. Talking is just so messy and chaotic.

AL: But one longs for that mess in a way. Certainly my interest in the way I make things is to see whether I can allow enough of the unsorted. It would be very nice to have more unsortedness. It’s very hard to do in writing.

LM: Right, or to make that public. The public—or sort of the institution—doesn’t often let you published something unsorted. [laughs]

AL: No, I know. It’s true. But I think again in the kind of sensibility that we’re all—well you and I—might be sharing has something to do without allowing for these extraneous or messy things that haven’t been brought into the organizational field. I’m really interested in that, and I’m interested in the idea of mistakes. And actually I’ve become really interested in this idea of opacity, true opacity, but I don’t actually know how to do it. In this world where everything is ineluctably apparent, I want things that are dis-apparent, you know. I disagree with this glut of access, of ostensible accessibility. It’s only ostensible, because if you rip everything out of its context, it has all the operations of a certain kind of instant recognizability, but no actual meaning.

LM: That makes me think again of the public because I think there is a way to convince the world, the public, the audience, and the reader that not getting it is incredibly productive, that that the act of hitting up against something opaque—as you described it—is and never understanding it is absolutely productive.

AL: Not only productive but actually fundamental. I mean, this is sort of a funny thing to say in relation to this thing of opacity, but there is some way where life comes up with these things that are inexplicable in the ways in which we’d like to explain things or the way in which our emotions respond to, something like this can never really find its way into some kind of iteration. You know, it’s a space of blankness or cessation, or I don’t know, it’s an endpoint.

LM: I would almost add “irrevocable,” to what you describe as inexplicable.

AL: Irrevocable is a really good word for that.

LM: Irrevocable and what that means because there’re so few things in life—or maybe there’s nothing in life—that’s irrevocable. And then there’s death, which is the only thing that’s irrevocable. But the experience of being alive and experiencing something that’s completely unchangeable in that sense completely opaque or inaccessible creates a kind of dark hole.

AL: Yes, I was going to use that rather fancy word “lacuna,” but it really is a kind of lacuna, a kind of gap. I think those gaps are important and need to be acknowledged and need to be folded into the way in which we understand life. I really feel very profoundly about that. And the call for something like consistency or wholeness or pure…

LM: …understanding…

AL: …yes, understanding.

LM: The word that also comes to me is “courage,” like you need a sense of courage to able to engage with irrevocability, but at the same time it’s not courage because as you know from grieving or from the experience you’re growing with, you’ve had no choice, you haven’t chosen this at all. So can it really be courage to confront this emptiness if you aren’t electing to be in this position at all?

AL: Well, yes, you can have a certain candor. I think we need a certain kind of candor that isn’t the same as honesty. It’s the candor of the wide open, the candor of facing it. And I think we need permission to be in these spaces, I think that’s really what I’m talking about. I want more permission to be overwhelmed by things that I can’t change or that I don’t know how to think or feel about or whatever.

LM: Absolutely. In these instances do you feel like writing is action?

AL: Well, I think language is a form of action, yes. It’s like another thing that Emerson says—“Words are a form of action”—I think he says that exact sentence. I want to think of my work as events and this is a sort of a basic aesthetic that we have that when we really have an experience of a work of art, whether it’s a poem or a painting or a piece of music. Something is happening to us, it’s an event, and it should affect us like an event …like we were one way before and now we’re something different afterward because it’s had this direct way of changing the molecules in the inner space somehow. So that’s a very tall order to say that you want your work to have the impact of an event or an action. If that’s the case, then the work can’t be fully a reaction, which goes back to the aboutness, right?

I talk to my students a lot about this because they don’t quite get it, I say to them: “You know the subject or the subject matter is absolutely autonomous, nobody else can have it. I can’t have your grandmother. I can’t have your sexual encounter. I can’t have anything actually that belongs to the ‘I.’ It’s all yours.” So then the subject is a wonderfully elaborated constellation that can emerge with someone saying “I,” but the “I” hardly can contain this multitude as somebody once said. And then I say, well, what is form in relation to that subject space, what is it supposed to do? And I think that that really interests me. That the formulation or the forming of something is a way in which we alleviate this absolute autonomy of ourselves, our “self-life.”

LM: I know exactly. You’re also talking about pleasure—the pleasure also for the reader having that experience of another. Of accumulating experiences, not information, of other selves.

AL: All we can hope for in a way is to make something more meaningful maybe, rather than knowable.

LM: Or complicate it so there’s more layers or more complexity or more experiences. That’s what’s so exciting about this idea of looking at the world with multiplicity—multiple perspectives, multiple solutions, or multiple histories. Then the complexity through which you see something is real fragmentation, it’s real facets.

AL: But also inside of that is the notion of letting go, of not holding tight, so tight to everything. If you let go a little bit, then it seems to me then you are also alleviating the necessity of a certain kind of recognition. I think that one of the things that is changing in the world that we’re in now is that people and artists are beginning to relent a little bit on their need to be totally identified with the things that they make in this way.

LM: And that no one’s role is more unique than the other. I think that’s a very optimistic in a way when you describe that you think the individuality of artists or the sense of the need for the eye in art is also changing.

AL: It is optimistic because it’s counter to marketing.

LM: Exactly. Anyways, it’s so nice to meet you by phone. And I can’t wait to meet in person. We’re taking baby steps you know.

AL: Yes, [baby steps]…but I’m very much looking forward to it.

This dialogue was organized by Marco Kane Braunschweiler and edited by Aria Dean, Karly Wildenhaus and Marco Kane Braunschweiler.