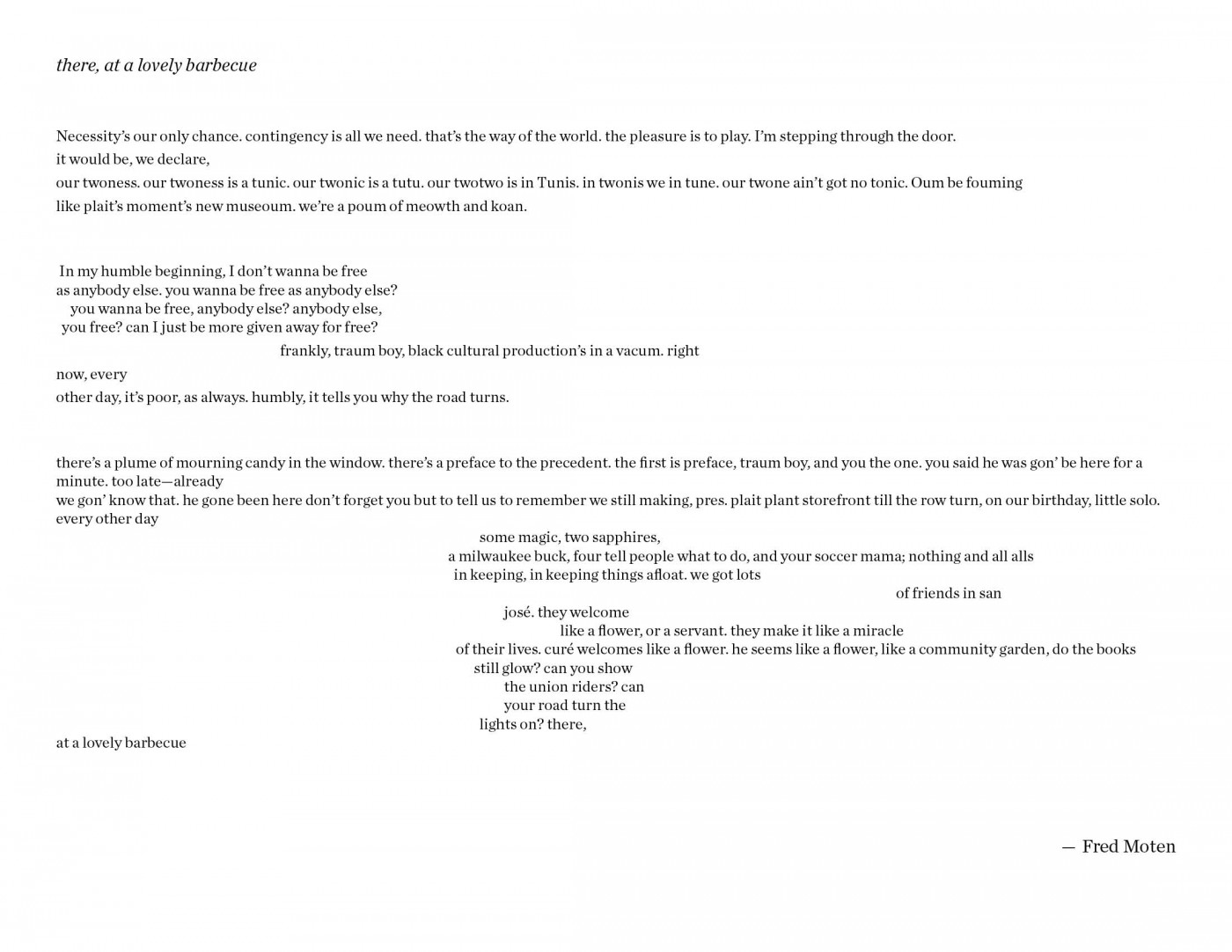

There is an analogy I have been trying to form in the interest of feigning narrative symmetry. How might I articulate that illness is to health as poetry is to the art it so often adorns? How might I claim that the sick are to the well as the poet is to the artist? Please remove, as you would the shoes you walk in, the presupposition that the sick are an impoverished version of the well. Neither the ill nor the poet need be martyred. “I mean,” says Keats, “Negative Capability, that is, when a man is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” Artists are not typically known to be agents of fact and reason. Poets, in this economy, perhaps less so even. But poets use words to mine mysteries and thus can provide language – the wardrobe of reason – to objects existing in space. (The market is implied in this transaction but I only have 200 words.) Illness mars the tabula rasa of health; the sick reify the status of the healthy. Do the poet and the ill distract from the uncertainties of art and health? This is my irritated reach.

The Poet and

The Critic,

and the missing

The poet prepares the public, an email. She rests it inside a server, its cradle. The poet prepares sanctions, trade agreements, adjusts her mask, some rhetoric on silence. Openness. The poet strips the community of land rights, mining rights, rites of love, and certain languages. In the small suburb of the poet’s feeling she prepares the colony. A prefix for those who would amend it. The poet prepares her notes in differing languages, all economic. The poet prepares a dinner where assurances will be made, interests aligned on the compound later. The poet prepares the contract, calls the signatories, checks the ships’ ledgers. The poet addresses the graduating class of the academy for international leadership. The poet uses of language nothing but an exquisitely coded terror. The poet prepares the nation, elegantly describing its borders. The poet is live from Athens, live from Dhaka, live from Frankfurt, live from Accra. Live from Guatemala City, live from Jakarta, live from Los Angeles, where she once undertook a youthful membership. The poet is live from the settler societies. The poet is live from the mountains, the valleys, the hotel banquet rooms of meetings about aid and development. The poet is live from elected bodies. The poet is live from unelected bodies. The poet is live from the central bank and the paintings that frame its lobby. The poet is live from the shareholder’s meeting, the desert retreat after. The poet is live from the judge’s chambers. The poet is live from international waters. The poet is live from the forest. The poet is live from the capitals, the coastline. The poet is live from the animal and from the mineral. The poet is live in the animal in the mineral the poet is live.

The Poet

Missing (Person) (s)

I did tell you the story but you’ve forgotten it.

You never told me the story.

We were walking along the Tiber, speaking of its wounds.

I have never been to Rome.

You remarked on the black nail polish all the women were wearing and on the youth of the musicians on the bridges.

You never told me the story.

You had said you wanted to know, to hear it for yourself. Were I to tell you the story again, would it matter?

Should it?

It’s hard to say.

What was the story about?

It was about a missing person, though actually it was about nothing.

How can there be a story about nothing?

It was just a story. It came to me as we were walking along the Bundt, after a drink at that writers’ bar.

I’ve never been to Shanghai.

Perhaps you were missing, a missing person in Shanghai.

How is that possible?

It’s possible in the story, if you think of it as the missing story.

You said it was dark, a dark story.

Maybe, maybe not – it was so long ago.

How long ago?

Weeks, years, it’s difficult to say.

Tell me anyway.

the missing

The Poet turns, sky halted, awkward. The Poet is arrested; The Poet rests.

The resting Poet watches the remaining sky. Sky fits into an empty basket marked The Poem. Sky papery, thinly lit by the bluish addendum of day. The Poet has a measure: day. The Poet finds a stone. The Poet puts the stone into the empty basket marked The Poem and collects up the rest: day, sky, and sea, all variously held by a bluish addendum. The Critic empties the basket marked The Poem of its stuff: stone, day, sea, sky. The empty basket is light. Night falls. Night falls and The Poet turns, awkwardly, toward the released sea. The sea is encrypted. The Poet cannot read the sea. The Poet hears the thwarted crescendo and places that into the empty basket marked The Poem. The basket churns heavily, awkwardly, heaving with the sound of the illegible sea and the that. The Poet sees that something is missing from the bluish turning into the arrested night sky, a missing that collapses into an addendum. The arrested Poet holds fast to the addendum. The basket marked The Poem rides out into the encrypted, unreadable sea.

The Poet

C:\> Criticality Status

This artist I know once started a sentence addressed to me like this: “within my criticality…”, which seemed like saying “in my experience” except saying it like a self regarding mass of atoms formed in the dense reactor core of an art school. Which – if we’re going to start splicing subatomic particles about it – is pretty much all I amount to as well.

See, it turns out we went to the same school – this artist and I -,although they must have paid more attention because I had to search “criticality” to find, it is a concept considered by Irit Rogoff (a professor at the school we both went to) who says, among other things “The old boundaries between making and theorizing, historicizing and displaying, criticizing and affirming have long been eroded.”

In other words – to be engaged in knowledge production – you ought to be everything and anything all at once; A chaos of being, a crozzled context, an avalanche of unknowing.

Of course it’s suspicious to casually hitch the language of two disciplines I know less than nothing about (in this instance, nuclear physics and critical theory) but “criticality” is the jargon of both and words are ours to play.

As an artist or as a nuclear physicist – your material is fissile or at least, the theory of such stuff. And as a milestone in the commissioning of a nuclear power plant – criticality is also “the state of a nuclear chain reacting medium when the chain reaction is self-sustaining (or critical), that is, when the reactivity is zero.” As sloppy masses of atoms held together by the vague notion of personhood, we are defined by the hot quantum mess we bump around, and inside of, and against. We will never be self sustaining. We are changed each time we are perceived and each time we sense. And the moment reactivity falls to zero – we become irrelevant – a notion that is an artist’s greatest fear and a critic’s favorite weapon.

The Critic

Photographs for newspapers were once transported like people: by plane, train, and boat. By the mid-1930s, the streamlining of the wire photo process allowed them to be sent through electrical impulses, over the telephone lines, in a matter of minutes. Fast photos for print journalism that was still slow; when only today’s evening or morning paper could provide the rejoinder to questions pending yesterday; the height of the hard copy. At newsstands, the world’s papers used to lay next to one another like keys on a piano. Following acoustics, the migration of a single image across their covers could become a note growing fainter with the distance from its origin. Here, a physical graph of one particular photo—the wearied eyes of a captured prime minister, yesterday claimed dead—mutating, contracting, shifting from left to right, from above to below the fold like a lone boat simultaneously docked with different precedence across the West’s ports, where other noteworthy vessels have names like Infant British Royalty, Hot Girls in a Tulip Field, Hot Girls on a Hydrofoil, Flooding in the Street, John Travolta’s Bedroom Eyes, Gerald and Betty Ford, Dead Body Covered by a Sheet, and many others, all long since news.

–

I found a hidden message written in a painting. I wonder if you saw it too. It’s one of those subtle, covert features snuck into the image like a penis in the background of a Disney cartoon. It nests within line and pictorial illusion in such a way that seems to evade general, unsuspecting viewing. Its visibility is tied to delay, appearing like a surprise that might be as effective subliminally at a quick glance or peripheral scan as upon longer, direct scrutiny.

For me, the message emerged well into a period of prolonged looking that was inevitable. There was basically no way I was not going to specially attend to this image. First of all, the painting has a long sightline in the museum through multiple galleries; you see it coming up ahead and move right towards it as you pass through doorways. Second of all, the painting is small and highly graphic, like a fist, and is paired with a roiling, raucous drawing by Lee Lozano, circa 1968. My Lozano obsession is well documented and continues unabated. Side by side and evenly sized, the two really dance together. The Lozano, on the right, is full of activity and innuendo that centers on a big pointy smile whose upturned crescent shape is echoed and flipped upside down in its partner to the left, the painting with the secret: Roy Lichtenstein’s Standing Rib from 1962. The Lichtenstein has a blank background around its single, snugly framed pop subject—a cut of bloody red steak, marbled with fat. The third reason I could not miss this painting is that the contemporary obscenity of eating animals on the scale that we do has been on my mind so much lately, even more than usual, mounting a long freak out inside me that’s reaching a breaking point. Expressions of desperation and despair: I have become hyper-sensitive to anything having to do with meat eating and all the crazy damage it does to human, animal, and planetary life. This is part of what it means to read a 1962 Roy Lichtenstein painting of steak in 2016.

–

The hidden message in Standing Rib is strange because it doesn’t say anything secret, in fact it actually just states the obvious, naming the picture of the thing in which it appears. Look in the thick strip of fat curving along the top of the painting, trace the cursive lines of white negative space there to read—meat. The ‘a’ and ‘t’ are clearest to me, but the whole word is unmistakable. Once seen, it can’t be ignored. Finding such a plain, basic, self-evident message is more about the hiding and burying of it than anything, it’s about meat as that emblematic thing that is shoved in our faces and so common and accepted that it goes unnoticed, unremarked upon, unquestioned, and unconsidered—mindlessly consumed. The elephant in every room where eating happens, it’s a fundamental problem that’s still easier in the short term for most people to ignore, but not for much longer. Meat: an obsolescing concept, a food whose gross negatives now far outweigh fleeting taste bud appeal. Lozano’s proximity here has something significant to teach; she cared about keeping track of numbers and quantities and was a real stickler for analyzing all forms of consumption:

Animal agriculture is the single biggest contributor of greenhouse gases to climate change, more than all transportation systems combined.

Not eating meat is the single biggest thing the average person can do for the environment.

Nearly 50% of California’s total water usage goes to animal agriculture, while only 4% goes to non-industrial uses.

23% of global freshwater is used just to grow livestock feed.

53 gallons of water go into the meat of one quarter-pound burger.

More water is saved by not eating one pound of beef than by not showering for six months.

Steak consumes about 16 times as much fossil fuel energy per calorie as plants.

Meat production produces 130 times as much waste as the entire population of America.

Animal protein increases the risk of cancer, heart disease, and alzheimers in humans; people who do not eat meat tend to live several years longer.

While reports vary on the numbers of animals killed every year for food, the quantities are unfathomably large, in the range of 8-10 billion land animals and 100 billion marine animals to feed the US alone.